Tumoral calcinosis simulating sarcoma

Sekhar S.1*, Shamili M.2, Gouthami B.3, Latha C.4, Harshitha G.5

DOI: https://doi.org/10.17511/jopm.2020.i01.15

1* S.V.R. Raja Sekhar, Assistant Professor, Department of Pathology, GEMS and Hospital, Srikakulam, Andhra Pradesh, India.

2 M. Shamili, Assistant Professor, Department of Pathology, GEMS and Hospital, Srikakulam, Andhra Pradesh, India.

3 B. Gouthami, Assistant Professor, Department of Pathology, GEMS and Hospital, Srikakulam, Andhra Pradesh, India.

4 Ch. Asha Latha, Assistant Professor, Department of Pathology, GEMS and Hospital, Srikakulam, Andhra Pradesh, India.

5 G. Harshitha, Postgraduate, Department of Pathology, GEMS and Hospital, Srikakulam, Andhra Pradesh, India.

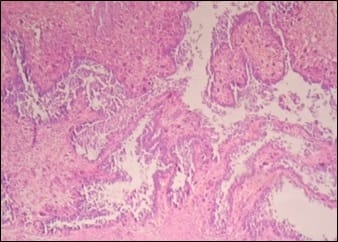

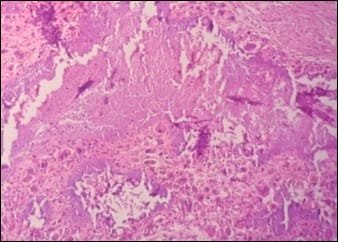

Tumoral calcinosis is a rare clinical and pathological entity, characterized by deposition of calcium in different sites of human body particularly in peri-articular tissues. It incidence is usually seen in young adults as a slowly growing, painless, firm to bony hard mass. Asymptomatic when small in size but larger masses can cause pressure symptoms due to compression of surrounding tissues or restriction of mobility of the joints. It can be predicted by typical radiological findings with the help of serum calcium and phosphorus levels but is confirmed only by histopathological examination. Many times, it isn’t very easy to diagnose this condition preoperatively and can be mistaken as soft tissue sarcoma both clinically and radiologically. Subtyping of this lesion depends on serum calcium, phosphorus levels, family history and co-morbid conditions like chronic renal failure.

Keywords: Tumoral calcinosis, Sarcoma, Serum calcium, Serum phosphorus

| Corresponding Author | How to Cite this Article | To Browse |

|---|---|---|

| , Assistant Professor, Department of Pathology, GEMS and Hospital, Srikakulam, Andhra Pradesh, India. Email: |

Sekhar SVRR , Shamili M, Gouthami B, Latha CA, Harshitha G. Tumoral calcinosis simulating sarcoma. Trop J Pathol Microbiol. 2020;6(1):93-97. Available From https://pathology.medresearch.in/index.php/jopm/article/view/392 |

©

©